About The Film

"When the film came out, the response was hideous," composer and musician Ed Bland says, when asked about his seminal short, The Cry of Jazz. "Very few liked it. The Marxists hated it 'cause it was independent of how they thought Blacks should think. But aside from me being called a Black fascist or whatever, a few people thought it quite unique."

Whether the effort was in film, music or intellectual thought, "unique" was often the result when Edward Osmund Bland—born July 25, 1926 on Chicago's south side—was at the helm. His mother, Althea, was a spiritualist, and his father, Edward, a US postal worker, dedicated Marxist, and known intellectual, who frequently hosted political meetings with such friends as Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright, Ulysses Kay, and Ralph Ellison at the Bland home.

Mr. Bland showed no interest in his father's politics, however, instead being wowed by the renowned music programs of DuSable High School, where he enrolled as a freshman. Settling on clarinet and saxophone, he quickly excelled and began seeking late night jam sessions around Chicago's south side. It was at one such Art Tatum jam session where Mr. Bland first heard Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," which would ultimately lead him to abandon performance and focus on composition, exclaiming "Why should I play only one instrument as a performer when as a composer, I can play the whole orchestra!" After serving in the Navy Band during WWII, Mr. Bland returned to Chicago, where he was hired to arrange and write for studio sessions at the blues-oriented Chess Records, and glimpsed pop music morphing into rock and roll.

He spent his days studying, hustling gigs, and spending many long nights debating with friends, Black and white, about the state of all things worldly, particularly in jazz. A more laid-back form of jazz stemming from the West Coast, performed and popularized mostly by whites and called by many West Coast or cool jazz, was hitting the airwaves. It seemed it was all that Bland's white peers—filmmakers, musicians, intellectuals—could talk about. "We'd hang out a lot at a bar called Jimmy's, and get in these arguments with all these jazz-critics-to-be," says Bland. "They were mostly white, and I felt there was a racial angle too; I felt they were trying to, shall we say, wipe the Blackness out of jazz. And they wouldn’t listen to us, so we decided to put it in stone."

The "us" was a motley crew consisting of Ed and three other Black friends: Mark Kennedy, Nelam Hill, and Eugene Titus—a novelist, city planner, and mathematician respectively—and though it would take several years for the seeds to sprout into a script, and then still a few more into celluloid, The Cry of Jazz would prove singularly iconoclastic. KHTB Productions (an acronym of each principal's last name) was born. Ed, himself now a postal worker, would direct, co-write, and produce the film, which was funded when "every two weeks or so, money came from one of our four paychecks," says Ed. "And of course we knew nothing about making a film."

Relying on dozens of volunteers to pull it off, the short—shot on 16mm for a cost of roughly $3500 and first screened in '59—is a monumental literal and figurative black-and-white dialectic that uses jazz as both lens and springboard for interpreting America's past, present, and future ills (and possibilities.) Black life is seen as a reflection of jazz and jazz as a reflection of Black life, all broken down by Black men who are not only their white peers' equals but clearly are schoolin' them. The blunt, didactic style pushes a jungle-fever tinged (hey, kickin' that knowledge is sexy!) history lesson that not only peeks into ghetto life on Chicago’s South Side—from the streets to the church to the pool halls and jazz clubs—but also presages, among many things, the popularity of rock and roll, the rapturous embrace of jazz by other countries, the American race riots of the late '60s, as well as, believe it or not, the evolution of hip-hop. True, no rappers, but the science of the loop is heard in full effect. Not to mention the rare live footage of Bland's friend, Le Sun Ra and his Arkestra, featured throughout.

The semi-documentary film caused a minor stir at screenings in Chicago and in New York City with its thesis that "jazz was dead." Esquire called it "a wretched little hymn of racial snobbery," whereas the London Observer's Kenneth Tynan wrote, "it is the first film in which the American Negro has issued a direct challenge to the white, claiming not merely equality but superiority.” Shortly after the film's debut NYC filmmaker Jonas Mekas (who would go on to create Anthology Film Archives) organized a roundtable discussion that included Bland, Nat Hentoff, Marshall Stearns, and Ralph Ellison. "Ellison hated it," Ed says. "I didn't realize he was interested in music. But I never knew it, 'cause he seemed to know nothing of music, and I told him that on stage. People got upset and called the police. That was the beginning of my life in New York."

Mekas later recruited Bland for his nascent New American Cinema Group, which included the likes of Shirley Clarke and Peter Bogdanovich. Mekas also invited him to write for his film journal, Film Culture, in order to further espouse the ideas explored in The Cry of Jazz. In the 1960 article, Bland wrote, "If Negro creators can transcend their present-day American demon thru the legacy left by dead jazz—if they can transcend their American experience with a total response instead of a minimal one, they will have executed a truly heroic act. And if white America can accept the Negro as the American hero, white America will have come of age." Bland was indeed interested in pursuing film, but his second screenplay, The American Hero, "went out to about 109 production companies and I got 109 rejections," he laughs. "So I thought I better get back to writing my own music."

And write music he did up until his death in 2013, at the age of 86. He applied what he learned at Chess Records to a number of record label and consulting jobs in New York City throughout the 1960s and '70s, including the Museum of Modern Art's "Jazz in the Garden" concert series, as well as at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and also became executive producer for Vanguard Records, where he recorded artists such as Elvin Jones, James Moody, Clark Terry, Big Mama Thornton, and the Pazant Brothers. Moreover, Ed Bland served as a presidential commissioner for the White House Record Library under President Carter, then later pursued Hollywood studio work in the 1980s. At the same time, he focused on his chamber and art music compositions, many of which would be performed by the Brooklyn Philharmonic, Detroit Symphony, and Baltimore Symphony among others. Decades later his work would be sampled by the likes of Cypress Hill, Fatboy Slim, and Beyoncé, among others.

The Cry of Jazz, however, is perhaps what he will best be remembered for. The film was inducted into the Library of Congress' National Film Registry in 2010, further solidifying the film's importance to American culture and beyond.

Restoration

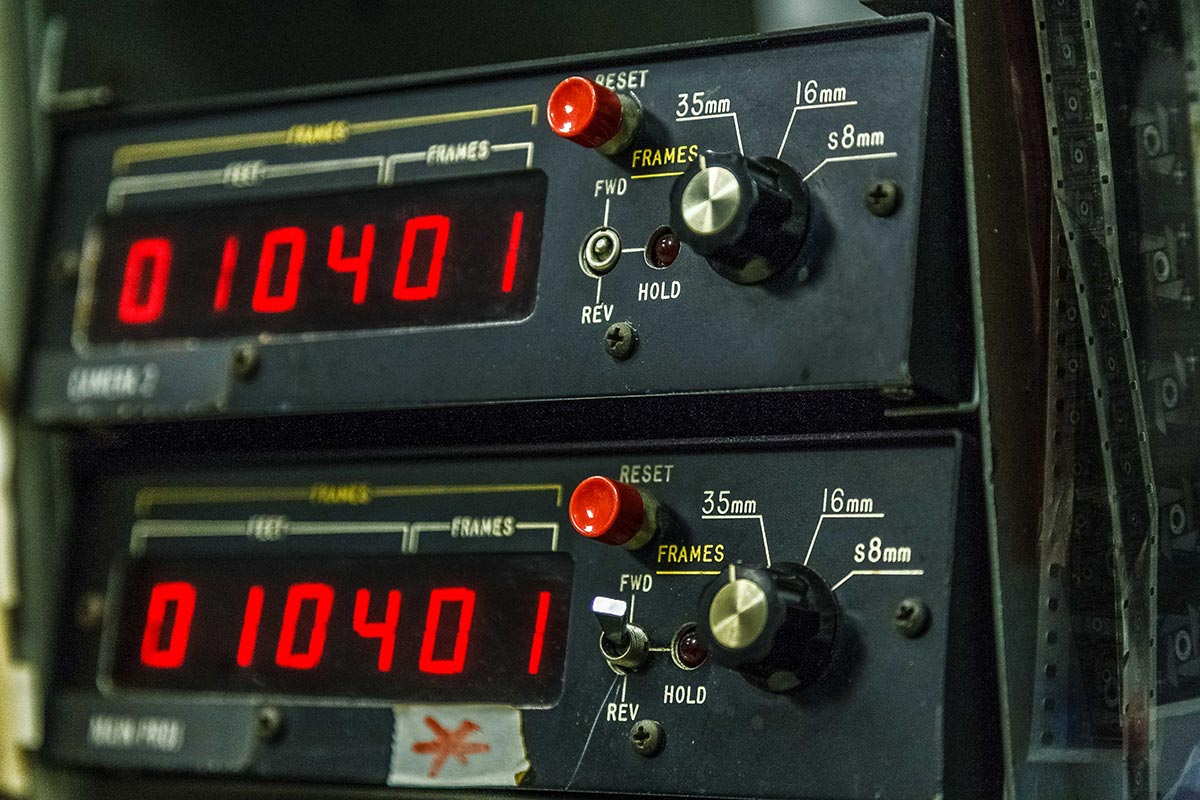

In 2010, The Cry of Jazz was restored and remastered with a grant from the Film Foundation, a process spearheaded by NYC's Anthology Film Archives. This intricate process involved both visual and audio restoration of the film. Colorlab handled the visual elements, while Bluwave Audio handled the audio elements. The "cleanest" 16mm print of the film was used as the basis for both stages of restoration.

At Colorlab, the process first entailed a deep liquid cleaning of the celluloid, after which it was re-shot—frame by frame—by a 35mm camera in order to create a previously non-existent 35mm negative. Meanwhile, the audio track of the film was worked on at Bluwave. This process entailed several stages. The first required digitizing the optical print, and then performing a second-by-second "scrubbing" of the soundtrack that aimed to remove unintended pops, clicks, and hiss. The result was then remixed and remastered in a separate sound theater to create a new digital audio master. Finally, a new optical soundtrack negative was created from this digital master in Bluwave's sound lab. The finished audio was then sent back to Colorlab, where the visual and audio were remarried to make a new 35mm print of The Cry of Jazz.